By Staff Reporter

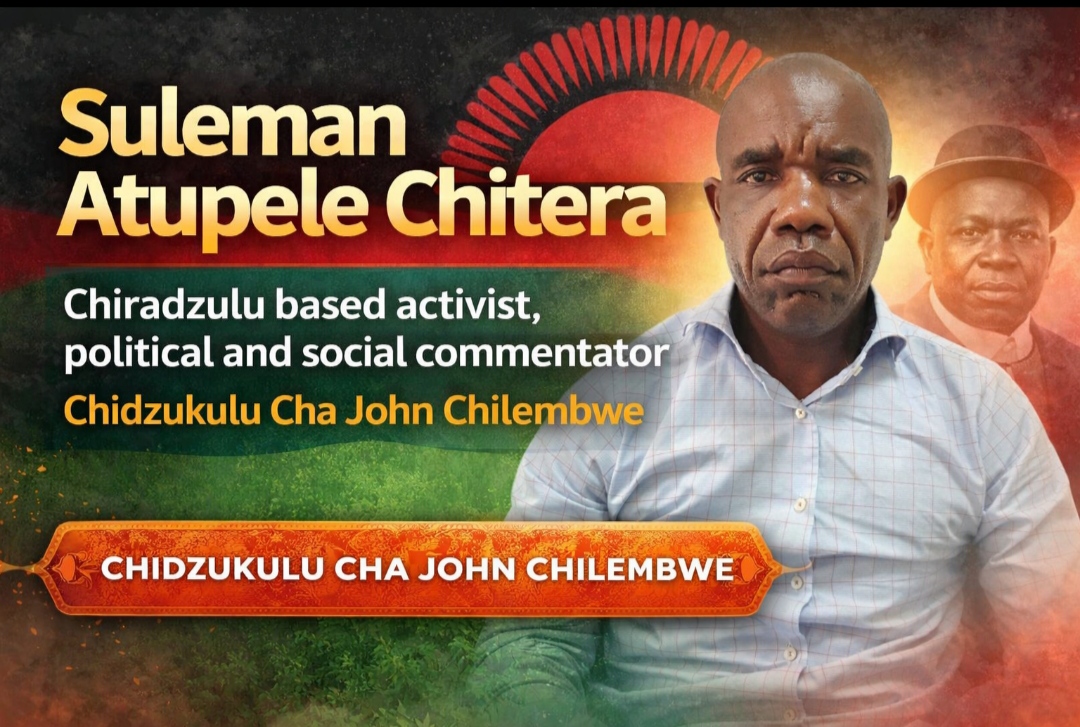

Chiradzulu-based political activist and social commentator Suleman Atupele Chitera has ignited a blunt but necessary debate: that Malawi’s laws are structured to suffocate the poor while shielding the powerful.

“The laws in Malawi were made to oppress the poor; there is no law that truly protects a poor person,” Chitera says—an indictment that resonates far beyond Chiradzulu, echoing in courtrooms, police stations, markets, and villages across the country.

For millions of Malawians struggling to survive on subsistence incomes, the law is less a shield than a weapon. Bail conditions they cannot afford, fines they cannot pay, and legal procedures they cannot navigate ensure that poverty itself becomes a punishable offence. Meanwhile, those with money and influence routinely bend the same laws to their advantage—delaying justice, securing injunctions, or walking free on technicalities.

Chitera argues that this is not accidental. It is structural.

“Our Constitution speaks the language of rights, but in practice it serves the elite,” he says. “If you are poor, the Constitution does not feed you, does not defend you, and does not stand between you and abuse of power.”

From land disputes where the poor are displaced with ease, to corruption cases where high-profile suspects enjoy prolonged freedom, the pattern is familiar. Justice moves swiftly against the weak and painfully slowly against the connected. Equality before the law exists largely on paper.

Chitera is calling for a serious constitutional review, one that goes beyond cosmetic amendments and confronts the economic realities of Malawians. He says legal protections must be deliberately redesigned to accommodate the poor—through accessible justice, stronger social and economic rights, and enforcement mechanisms that do not depend on wealth.

“A Constitution that does not protect the poor is not progressive—it is performative,” he says.

His remarks come at a time when public frustration is boiling over, fueled by rising living costs, unemployment, and a widening gap between political promises and lived reality. For many, the law has become another institution that reminds them of their powerlessness.

Chitera’s message is uncomfortable, but it is timely. Malawi must decide whether its laws will continue to entrench inequality or be reshaped to serve the majority who live on the margins. Until then, the poor will keep learning the same harsh lesson: in Malawi, justice is affordable—but only if you have money.