By Burnett Munthali

The Malawian government has announced that fuel under the Government-to-Government (G2G) agreement is expected to arrive in the country this July.

This revelation comes amid persistent fuel shortages that have crippled key sectors of the economy and intensified public frustration across the nation.

For many Malawians, especially those in transport, agriculture, and small-scale businesses, the promise of fuel arriving in July offers a glimmer of hope after months of unpredictable supply and long queues at service stations.

The G2G arrangement, which typically involves a bilateral fuel import deal between Malawi and a foreign government, is seen as a strategic move to bypass commercial market constraints and secure more stable access to petroleum products.

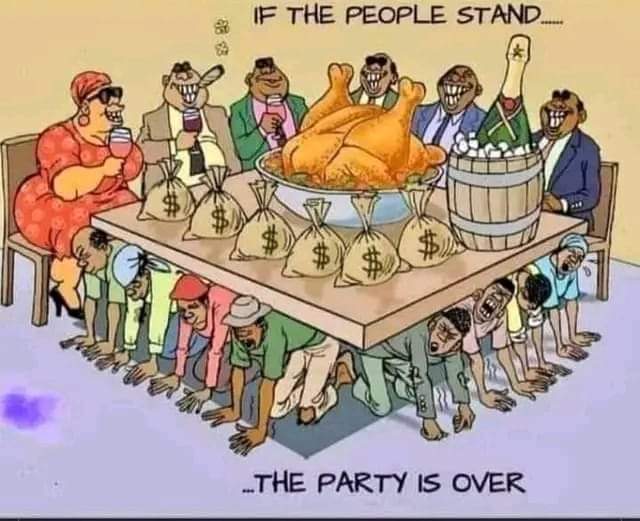

However, questions linger about the transparency, sustainability, and execution of this deal—particularly in a country where previous fuel procurement efforts have often been mired in bureaucratic delays, logistical setbacks, and allegations of corruption.

The Ministry of Energy has yet to disclose the finer details of the G2G agreement, including the identity of the supplying country, volume of fuel expected, pricing structure, and payment terms.

This lack of information fuels speculation about whether the deal is a stopgap political maneuver or a carefully crafted solution to a systemic problem.

The history of G2G fuel deals in Malawi is not without controversy; similar arrangements in the past have faced criticism for being rushed, opaque, and prone to mismanagement.

The public is justified in demanding accountability, given that the recurring fuel crises have far-reaching impacts—not just on the economy but also on health services, food distribution, and education.

In rural areas, the absence of reliable fuel access translates to delayed deliveries of medical supplies and agricultural inputs, further deepening the cycle of poverty.

Urban dwellers, meanwhile, grapple with inflated transport fares, interrupted livelihoods, and power outages due to diesel shortages at generator-reliant facilities.

Some economic analysts argue that the government’s overreliance on G2G deals points to a deeper problem: the lack of a long-term, diversified fuel importation and energy security strategy.

Others point to foreign exchange scarcity as the root cause, arguing that unless Malawi boosts export earnings or receives significant donor support, even the G2G deal may only offer temporary relief.

It also remains unclear whether the National Oil Company of Malawi (NOCMA) has the logistical capacity to handle, distribute, and monitor the incoming fuel efficiently.

The July delivery, if it materializes, could be a key litmus test for both NOCMA and the Ministry of Energy in terms of planning, coordination, and communication with the public.

Failure to meet expectations will likely deepen public distrust in government promises and further damage confidence in national institutions.

On the flip side, successful execution could restore some faith and offer lessons on how to structure future energy procurement frameworks.

Ultimately, the impending arrival of G2G fuel should not be celebrated prematurely but should instead prompt urgent dialogue about structural reforms in Malawi’s fuel procurement and energy management systems.

A lasting solution will require a combination of diplomatic negotiation, economic discipline, investment in renewable alternatives, and firm political will.

Until then, Malawians continue to wait—anxiously and wearily—for the promise of July to become a reality, not another chapter in the country’s long-running fuel nightmare.