By Kakwe Mkaulire

Since assuming office following the landmark 2025 elections, President Arthur Peter Mutharika has faced broad domestic scrutiny over his cabinet appointments. Among numerous criticisms — including allegations of regional bias and political patronage — a persistent question has emerged: Have Muslims in Malawi been marginalised in the composition of the new cabinet?

This report examines the basis for such claims, analyses factual evidence on appointments, and contextualises perceptions within Malawi’s social and political landscape.

Context: Malawi’s Political and Religious Landscape

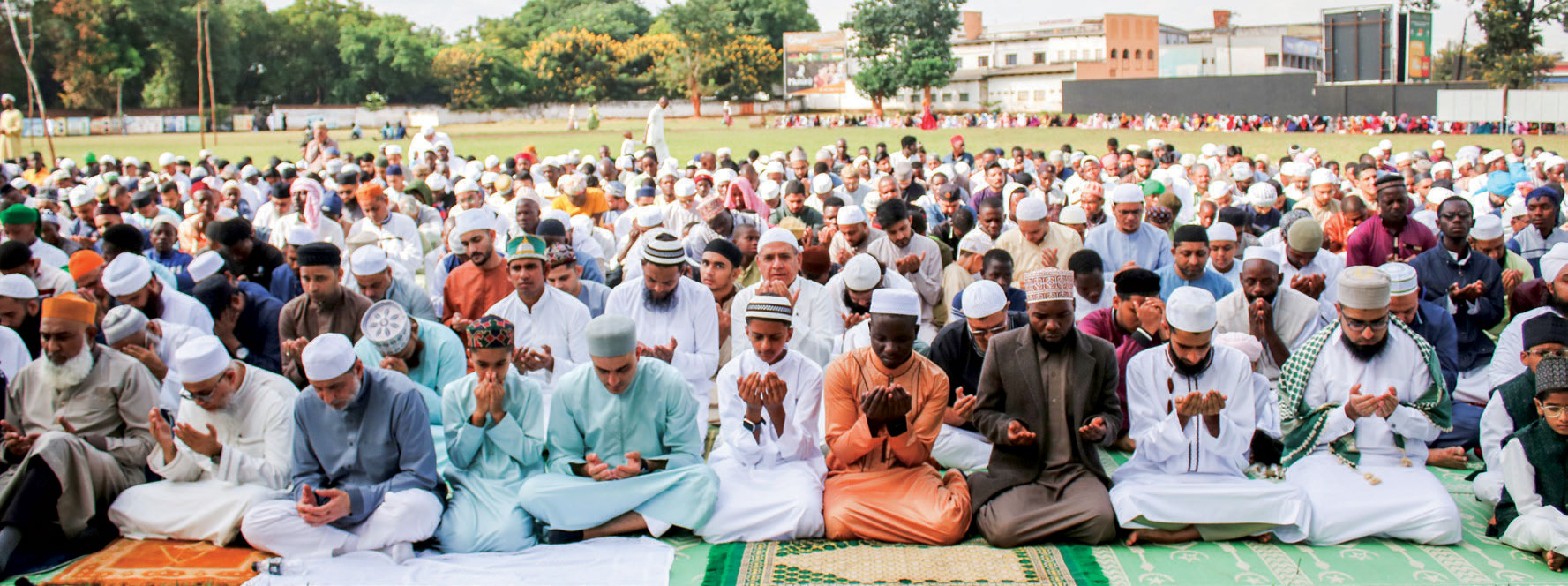

Malawi is a religiously diverse nation where Christians form the majority and Muslims constitute a significant minority. Historically, successive administrations have varied in how they engage with and include Muslim leaders and communities in political structures and public appointments.

While the constitution guarantees freedom of religion and equal opportunity, political representation can shape public perceptions of inclusion, especially in national leadership.

Composition of the Mutharika Cabinet

Following his inauguration, President Mutharika announced his cabinet in phases. Initial appointments included key portfolios such as Finance, Foreign Affairs, and State, with leaders drawn largely from his political alliance partners and longstanding Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) figures.

Subsequent cabinet lists confirmed a full contingent of ministers and deputies, but there has been no widely reported official breakdown showing significant Muslim appointments. Government releases and independent reporting to date do not emphasise inclusion by religion or explicitly note prominent Muslim figures among the top ministerial team.

At the same time, civil society and partisan critics have focused more on regional imbalance and political patronage than on religious representation per se. Observers have noted that the cabinet’s size and composition leaned heavily toward political allies and regional strongholds of the president, rather than being reflective of Malawi’s full societal diversity.

Claims of Marginalisation by Religious Organisations

Voices within sections of the Muslim community have raised concerns about representation beyond formal appointments:

- Historical Grievances: In previous decades, Islamic organisations such as the Central Islamic Society (CIS) — affiliated with the Muslim Association of Malawi (MAM) — publicly claimed that under former President Mutharika’s earlier administrations, Muslims were systematically sidelined in appointments to public boards, commissions, and relief distribution. These sentiments were met with official rebuttals from State House, which maintained that Muslims were accorded equal opportunity.

These past claims continue to circulate in Muslim public discourse and are sometimes invoked when analysing contemporary governance, but it remains less clear whether similar patterns have been quantitatively demonstrated in the latest cabinet appointments.

Perceptions Versus Confirmed Data

Critics within and outside the Muslim community have articulated the idea of marginalisation based on perceptions of absence or limited presence in senior political positions. This can stem from:

- A lack of visible Muslim ministers in high-profile ministerial portfolios.

- Legacy narratives inherited from earlier governments.

- Unverified but circulating public sentiment that appointments do not reflect Malawi’s religious diversity.

However, there is currently no authoritative public data listing the religious identities of all cabinet appointees under the 2025 Mutharika administration, nor any official statement from constitutional institutions confirming religious targeting or exclusion. The National Cabinet list as published does not categorically identify faith affiliations for individual ministers.

Expert Perspectives on Representation

Policy analysts and scholars note that in many multi-faith societies, representation issues often arise from political alliances, electoral demographics, and party structures, rather than explicit religious discrimination. Cabinet composition is generally shaped by political coalition building, regional considerations, and internal party agreements. This can result in under-representation of particular groups without necessarily constituting deliberate exclusion.

At the same time, perceptions of exclusion matter politically and socially, particularly if a significant community feels its interests are not reflected at the highest levels of governance.

Conclusion: Sidelined or Underrepresented?

The claim that Muslims are being sidelined in President Mutharika’s cabinet is difficult to conclusively substantiate on the basis of available public data:

- Confirmed Data: Cabinet appointments have been publicised; however, there is no official accounting of appointees by religion.

- Perception of Exclusion: Some community voices point to a lack of visible Muslim representation and broader patterns they perceive as exclusionary.

- Historical Context: Past claims of religious marginalisation under Mutharika’s earlier tenure persist in public memory and inform current narratives.

Without an official breakdown or targeted policy analysis, it remains more precise to describe the situation as perceived under-representation and concern about inclusivity rather than verified systemic sidelining on the basis of religion alone.

For deeper clarity, further reporting could compile a religion-annotated list of cabinet appointees and compare representation with demographic data, or include interviews with Muslim civil society leaders and Mutharika administration officials.