By Burnett Munthali

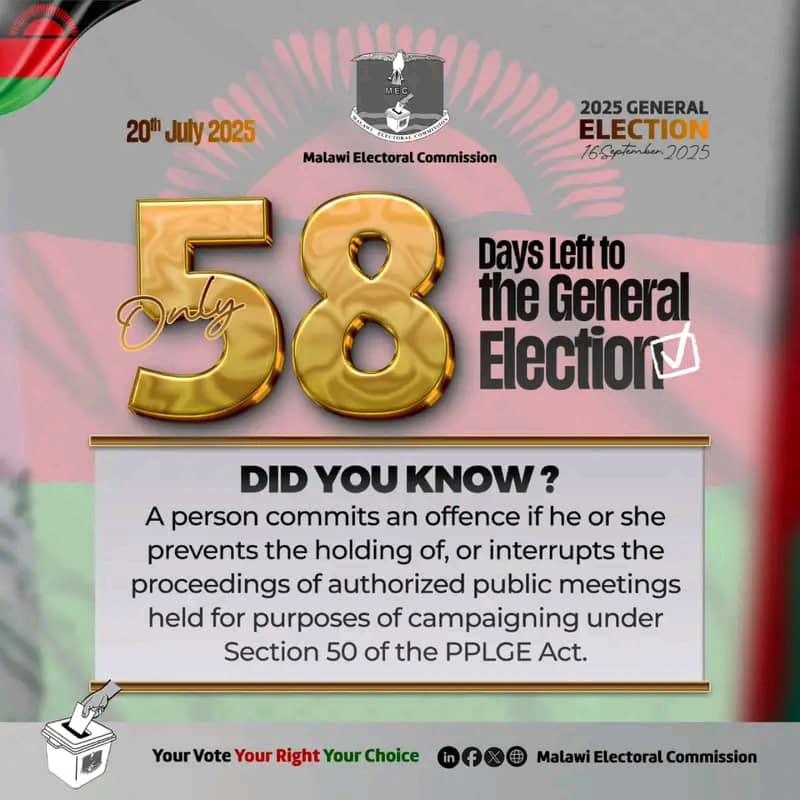

On 20 July 2025, the Malawi Electoral Commission (MEC) reminded the nation that just 58 days remain before Malawians cast their ballots in the 16 September 2025 General Election.

The countdown sharpened national focus on whether electoral preparations are keeping pace with the calendar.

The announcement also underscored that the window for formal submission of nomination papers runs from 24 to 30 July 2025 across designated centres nationwide.

Because Malawi votes on the same day for President, Members of Parliament, and Local Government Councillors, any bottlenecks in the nomination process can cascade into ballot design delays, compressed procurement, legal disputes, and voter confusion.

MEC has already revised elements of the electoral calendar to align nomination activities with the constitutional dissolution of Parliament and Local Councils.

The Commission says the adjustment protects legal integrity and gives stakeholders a fairer preparation runway.

MEC’s public notice further explains that candidates or their authorised representatives may request pre‑inspection of nomination papers so defects can be corrected before the submission deadline.

That procedural safeguard, if widely used, can dramatically cut last‑minute disqualifications and costly litigation.

Pre‑inspection windows have been flagged in MEC communications and echoed in media reporting, with presidential nomination checks slated at Commission Head Office in the days leading into the formal receipt period.

Election administrators everywhere know that most technical disputes spring from paperwork errors—missing signatures, incomplete asset declarations, or faulty party authorisations—and Malawi is no exception.

That is why the period before nominations must be treated by political parties as an internal compliance sprint, not a ceremonial pause.

Confusion has already surfaced after earlier messaging on nomination timing circulated before MEC finalised its revision.

Mixed communications can easily mislead aspirants who lack professional legal teams or central party guidance.

With the official campaign season running 14 July to 14 September 2025, nomination logistics and campaign scheduling are now tightly intertwined.

Poor sequencing, double‑booked venues, or disputed rally permits could inflame tensions just as parties need calm to complete filings.

MEC has warned that disrupting authorised campaign events constitutes an offence and has urged restraint as political temperatures rise.

Legal clarity also matters for ballot confidence.

MEC’s June briefing confirmed that polling stations will open at 6:00 a.m. and close at 4:00 p.m., with all voters still in queue at closing allowed to cast ballots.

That operational rule needs relentless repetition in civic education so no voter abandons the line prematurely.

The same briefing reiterated that the list of duly nominated candidates must be gazetted and published by 8 August 2025.

That leaves a narrow production runway for ballot printing, quality checks, distribution, and voter education materials.

Tight timelines inevitably amplify risk in technology, logistics, and dispute resolution.

Malawi enters this phase with unresolved tensions over the election management system supplied by Smartmatic.

Opposition parties across the spectrum have pushed for an independent technical audit, arguing that transparency is essential to public trust in a competitive race.

MEC has resisted broad external access, citing institutional independence, system security, and weaknesses in the proposed audit scope.

The intensity of the dispute suggests it will shadow the nomination and campaign periods unless mediated.

Grassroots pressure has added fire, with activist Bon Kalindo and the Malawi First movement threatening mobilisation—and even calling for a fallback to manual voting—if confidence in the technology is not restored.

The technology debate is not a sideshow.

Contested systems multiply post‑election petitions and can delegitimise outcomes even when the underlying vote count is sound.

To its credit, MEC has engaged regional and international observer missions, including the African Union, COMESA, the European Union, and the SADC Electoral Advisory Council.

Observer engagement strengthens transparency norms but cannot substitute for domestic party buy‑in on procedures, technology, and results transmission.

Malawi’s 50+1 presidential threshold means tight margins magnify incentives to contest process weaknesses.

The revised calendar now compresses critical tasks for parties: vet candidates, settle internal disputes, collect valid signatures, pay nomination fees, and deliver complete paperwork to the correct district and constituency centres.

For smaller parties and independent aspirants who lack legal departments, MEC field offices and civil society help desks will be decisive in preventing paperwork collapses that disenfranchise communities.

Media houses should immediately roll out “Know Your Nomination Requirements” explainers—short, plain‑language checklists in Chichewa, Tumbuka, Yao, and English.

Election preparedness is also a citizen responsibility.

Communities should confirm that polling locations remain accessible, that voter transfer corrections were captured, and that emerging campaign clashes are reported early to district security committees.

Because deadlines are unforgiving, any candidate who waits until the final 48 hours of the 24–30 July window to submit papers is choosing to gamble with technical disqualification.

Where parties anticipate litigation—over boundaries, eligibility, or symbol duplication—they should file early to preserve time for correction and appeal before ballots go to print.

Voter confidence will hinge on visible problem‑solving: quick cure of defective papers, transparent publication of approved candidate lists, and open communication when disputes arise.

Malawi’s recent history—including the 2020 Constitutional Court ruling that reset expectations for electoral legality—means the public now demands verifiable adherence to procedure, not deferential trust.

If MEC manages nominations cleanly, it will bank credibility that will prove invaluable should close results trigger recounts or court challenges in September.

If the nomination stage is marred by confusion, inconsistent guidance, or perceptions of selective enforcement, the legitimacy of the final outcome will be contested long before a single vote is counted.

The 58‑day marker is therefore more than a countdown graphic; it is a governance alarm reminding institutions, parties, media, and citizens that the integrity of Election Day is built—or broken—in the nomination room.

Malawi has the advantage of an election body that is publishing schedules, inviting observers, and offering pre‑inspection.

It must now close the loop with responsive outreach, consistent enforcement, and real‑time problem solving.

Parties that aspire to govern must prove they can follow the rules before asking to write them.

Citizens who value their vote must watch these next ten days as closely as they will guard the ballot boxes in September.